On Tuesday I was at one of Sprinklr‘s #social@scale events in London. These are always good because a series of big brands (who happen to be Sprinklr clients of course) basically spill the beans on what they are up to in social media.

On Tuesday I was at one of Sprinklr‘s #social@scale events in London. These are always good because a series of big brands (who happen to be Sprinklr clients of course) basically spill the beans on what they are up to in social media.

The stand out presentation (no offence to the other presenters) was adidas who spilled the beans on their World Cup programme. It was fascinating because, firstly it was adidas, secondly it was the World Cup (the biggest potential brand exposure platform there is, especially for a sports brand) and thirdly, what an astonishing tin of beans it was.

To give you a flavour: the strategy had three elements, mobilization, anticipation and reaction. On the mobilization front they set up a social media command centre in Rio with a team of 80 people. 80 people! To put that into perspective the England national team only brought an entourage of 72 people – and that was the largest party England had ever assembled. From this command centre adidas were running a broadcast/content operation that was probably more extensive (in terms of its usage of channel and variety of output) than any of the traditional media broadcasters, although they didn’t trump the BBCs’ 272 people in terms of numbers. But I don’t think anyone trumps the BBC in terms of the numbers of people turning up at these sorts of parties.

In terms of anticipation adidas went there having prepared what they called a content bible: actually a vast library of material ‘in the can’, so that they could react in real time to almost any scenario. They also did something that was super-clever in order to get around the fact that they didn’t own the rights to any of the content from the games themselves, which was to have an animation facility on tap that could produce stylised video representations of the key moments of play which could then be put out as vines or assembled into montages for YouTube. In many ways these were even more ‘engaging’ than the real video clips because they challenged the viewer to match the clip and the players featured with the actual moments of play they were recreating. Making your audience work for the punch line always gets bigger laughs than just spoon-feeding them jokes.

And to give an indication of the speed of reaction, the Bazuca ball had its own Twitter identity. Come the infamous ‘was it over the line’ incident, ‘the ball’ tweeted that it was a goal before even the referee made his decision. Whether or not you think giving a ball a Twitter identity is a good idea you have to take your hat off to the speed of reaction.

Basically the whole thing was totally awesome in scale and organisation. In fact it was probably the most totally awesome way in which you could use social media, if you wished to use social media in a totally awesome way. Indeed this may even set a never to be repeated high watermark for social media awesomeness.

Why never to be repeated? Well here is where it gets interesting. The objective for all this awesomeness was simply to “have the loudest voice at the World Cup” according to @KrisEkman who was giving the presentation. So at the end of the presentation I asked the question, “why was this the objective and how did you measure it – was it just with respect to the share of voice of competitor brands or was it with respect to the whole World Cup conversation on social media?” The answer, it transpired, was basically to be shouting louder than Nike. This was because Nike was perceived to have ‘won’ the last World Cup and adidas wanted to out-gun them this time. And then came the killer question from Jessica Federer (@jjfeds) from Bayer. “How did you justify this expenditure to the bosses, in terms of what it did for sales or brand reputation” she said. The answer was startling. “We didn’t have to do this”, said Kris. Basically the team had been given an ROI pass: the whole thing had been declared an ROI-free zone. All they had to do was rack-up was more engagement stats than Nike.

Wow. Is that enlightened or just plain crazy? Not only were adidas spending a huge amount of money on a hunch, they were unable to have any basis for comparison for what a campaign vectored almost exclusively in social media was delivering versus what a traditional media based campaign would have delivered. Wow.

This seemed to me the equivalent of a football manager saying “you don’t have to score any goals, just make more passes than anyone else.” I tackled Kris in a coffee break on this one. Of course, it wasn’t a totally measurement free zone. The fact that they were using a platform such as Sprinklr to manage all the listening and response channels meant that they had control over a lot of the data. For example they could track contacts in social media through to online sales, albeit as Kris acknowledged, this was really only a small part of the picture. Now while Sprinklr does a good job on measurement, its main function is for real-time management and control. It can provide you with data you can plug into measurement processes if you want to, but, as far as I was aware, the Sprinklr data wasn’t really being plugged into anything. Ultimately, adidas will also be able to look at uplift in sales and compare this to that generated by previous World Cup or Euro campaigns. Perhaps they already have this picture. None-the-less, this was a pretty big leap of faith.

As an aside, measurement is my big beef with many brands’ usage of social media. For example, everyone is spending big bucks producing loads of ‘content’ but no-one can measure the value the individual pieces of content created. Therefore you neither get a decent ROI calculation nor do you have an editorial framework that allows you decide which types of content you should be creating, i.e. which bits create the most value.

For myself, I didn’t quite know what to make of the adidas campaign. I was blown away by the awesomeness, but fear it may not have won the battle of sales, even if it won the battle of shouting. I always carry on about there now being two worlds for brands: the world of the audience (which is what traditional marketing has always been about) and the world of the individual (the new space where social media plays). Audiences don’t really exist in social media and to the extent to which they do, they are quite hard to create. For an event like the World Cup, which is probably the biggest audience-based event on the planet, is it therefore appropriate to show-up with an approach that, no matter what awesome levels of investment you throw at it, is always going to struggle to reach an audience as big as that which is available through more traditional channels? (Remembering, of course that social media isn’t really a channel or form of media, it is an infrastructure).

For sure, social media must form an important part of any campaign. Social media is a participatory media, it allows you to do things with groups of consumers or individuals that are not possible when you are simply ‘performing’ in traditional media, or ‘reaching out’ in competitions, promotions, events etc. But what it delivers in terms of participatory opportunity, it tends to lack in terms of reach.

It was interesting to note that very few of the 50 or so people in the room had seen the elements of adidas’s campaign. I must confess that I hadn’t encountered any of it. Put together all the elements in a show-reel and it looks totally awesome – but no consumer ever gets to see the show-reel. This is always a challenge, even if you are creating a campaign that has a higher dependency on high-reach media. But the way you solve this is by having a well-defined central creative idea, such that when a consumer sees just a bit of the campaign, it reinforces or creates the pathway back to that central idea. The idea acts as a multiplier to the individual tactics. Without this, you just have a bunch of tactics.

What then was the adidas idea? The tag line was ‘All in or nothing’ but this is a one-line expression of an idea not the idea itself. The difficulty I think adidas faced is that it is hard to make social media conform to the strictures of carrying an idea. You can use it to help create an idea or to involve people in aspects of that idea, but traditional forms of broadcast channel or conventional audience-based marketing activities are almost always better vehicles for actually driving an idea. Social media is also relentlessly real-time: a fact that adidas’s approach was set up to deal with. But it is hard to exert the creative precision necessary to sustain an idea, when you have only seconds to react. It is a bit like being asked a question, but then having to frame your answer in rhyme and also sing it as a jingle. Quite possibly adidas’s reliance (over-reliance?) on social media actually ended up eroding the focus on a creative idea (because singing all your responses in rhyme and in real-time is just too creatively challenging).

So I was left with the question: are adidas simply doing the wrong thing, brilliantly? At heart, it was a conventional broadcast strategy that used social, rather than traditional, media channels. But as we all know by now, social media is not about broadcast (it’s not even really media). You may well be shouting louder than Nike, but social media is not a medium for shouting.

And this is why I suspect this awesome display may represent the high-water mark: for adidas and perhaps all brands. For sure, they went #allin and whilst they didn’t get nothing, when they look at the sales lift, did they get enough?

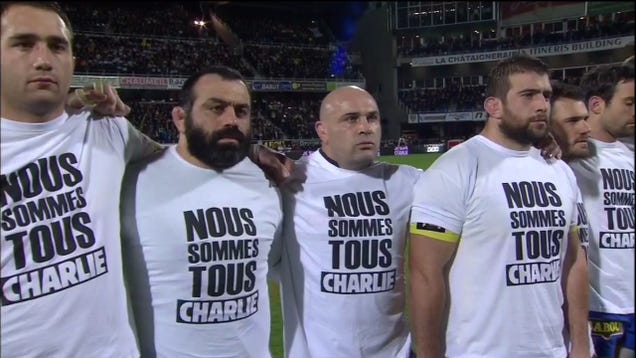

This week , the magazine Charlie Hebdo will publish a defiant response to the terrorists who assassinated 8 members of its staff and four shoppers in a Jewish supermarket. This response will involve publishing an image of the Prophet Muhammad.

This week , the magazine Charlie Hebdo will publish a defiant response to the terrorists who assassinated 8 members of its staff and four shoppers in a Jewish supermarket. This response will involve publishing an image of the Prophet Muhammad.