Everyone is getting a bit obsessed by Klout at the moment. It is easy to see why. Social media (or in fact social life) now has its equivalent of a golf handicap bringing with it the potential for obsession based on trying to improve your score. And from a brand’s perspective, there is seduction in the belief that you can identify and exploit the small group of consumers or customers who are seen to be ‘digital influencers’ tapping into the almost mythical, but often tantalisingly out-of-reach, power of ‘word-of-mouth’ and ‘peer recommendation’ . This recent Wired article probably sums up state of play.

There is also significant community of Klout knockers out there. As this article by Jason Falls outlines, this whole issue of digital influence has the potential to create socially undesirable discrimination. There are also others, such as danah boyd, who have pointed out the often self-defeating nature of an individual’s quest for digital influence, because of the potential to game the system – creating scores that bear no real resemblance to any ability to create an actual effect. This seems to me to be the influencer equivalent of Hugh’s Law (Hugh Macleod’s contention that all social networks eventually descend into a swampy mass of spam). Perhaps we should call in danah’s Law.

While I sympathise with the critics, I can’t help feeling that this whole issue will go away for the very simple reason that we will discover that digital influence is probably not the same thing as digital importance – and therefore not very important in the wider scheme of things

Here is what I mean. Which of these two people might be the most important to your business – a person your influencer strategy has identified as having a high potential ability to spread the message about your brand through digital networks, or a person with very little pre-determined influence but who happens to be the first to spot and tweet about a problem with your product or service? Or, say, a person who has asked a question for which your business provides an answer – someone who, through their digital behaviour, has identified themselves as a potential customer? For me it is obvious – while the former is a person with high potential influence the latter is someone with high actual importance albeit low pre-determined digital influence. Critically, the former is defined by who they are (something than remains fixed over time), whereas the latter is defined by what they are doing at any one moment in time (behaviours and context).

Consider this. Dave Carroll, the musician who made the famous video song about United Airways breaking his guitar was not a digital influencer. No strategy designed to identify the high digital influencers within United’s customer base would have picked him up. However, he became hugely influential, or more accurately hugely important, to United because of what happened to him (context) and what he then did (behaviours) and also what United did or failed to do (behaviours again).

This suggest to me an important principle. Within traditional media influence and importance were the same thing whereas with social media they have become separated. This is a practical observation, but it conforms to the theory – that theory being the fact that Gutenberg created an enduring marriage between content and channels, information and distribution. Channels had fixed and measurable levels of influence: attach your message to a channel (or influencer) and the message could then ride on the influence the channel brought with it. The name of the game was therefore all about marrying your message with the most influential channels (or to the most influential people). However social media is all about the separation of information from the means of distribution – the breaking of the Gutenberg relationship. Thus the importance of information is not defined by the channels it sits within, but more by the context from which it comes.

End of theory, let’s look at more practice.

The Alitmeter Group’s Brian Solis has just produced an excellent report called The Rise of Digital Influence. This is probably the most detailed description of the topic around – and I recommend that you read it. However, this report and indeed most of the current discussion around digital influence, rests upon two assumptions. These are: first, that digital influence is vested in an identifiable and relatively small group of individuals (digital influencers); and second, that the role or importance of these influencers is as information amplifiers or distributers – spreading information about a brand through their network. I think the case I have presented earlier gives sufficient reason to doubt the first of these assumptions because, no matter how influential these individuals may appear, they are not actually that important (because importance has become separated from influence).

But what about the second assumption – the idea that the role of a digital influencer is as a distributer or amplifier of a brand message? Perhaps the best way to examine this is to see where this idea might have come from. In the world of traditional media the role of media was as a channel – it was a means of distributing information. Therefore its effectiveness (influence) was assessed on its ability to reach the maximum number of relevant people. Applying this approach to the social digital space, we have realised (some have anyway) that Twitter and Facebook are not really forms of media or even channels, but that they are tools that people use to distribute information. Thus it is people that are the closest thing, within social media, to what represented a channel in traditional media. Thus applying the old thinking, the value of a channel lies in its ability to distribute information, thus the assumption that the value of a person in social media should be assessed the same way. This assumption has great appeal, because it allows us to export most of the strategies and approaches we have become familiar with in the traditional media space, into the social space. We don’t have to re-invent things, challenge our thinking or develop new approaches. But this is to fall into one of the classic mistakes that so many are making when trying to enter the social digital space, namely restricting our ability to understand the new space by our desire to make it appear and behave like the old space we understood. It is the thinking that lead many to assume that the way you use a Facebook page is to try and turn it into a website.

It also has an appeal in that there is already a large commercial sector out there developing and selling us the tools to identify and exploit digital influencers. These are the people Brain Solis cites in his report as Digital Influence Vendors. Interestingly, Brian’s methodology is as follows:

- Qualitative interviews and software demos with a total of 20 vendors

- Qualitative reviews of 17 services provided by included vendors

- Qualitative reviews of six brands that have piloted digital influencer programmes

- Quantitative study of vendor features against key criteria of influencer engagement.

This heavy reliance upon the vendors as the source of his information must, in large part, therefore influence his conclusions (in fact in responding to comments on his blog, Brian has acknowledged that this report is actually more an investigation of the vendors and overview of how best to use these products, which is still a useful exercise provided you buy into the assumptions I have already mentioned).

There is a further problem. Even if we are right to assume that the role of a digital influencer is as an information distributer or amplifier – how powerful are these people likely to be? In the traditional media space, if you marry your message to a channel, that channel will be guaranteed to carry the message to the audience. No such guarantee exists in social media. If a brand identifies you as an influencer, and sends you information or even provides you with an incentive or a reward, why should you bother to pass the information on? You are being rewarded for your influence, not for using that influence. The only behaviour that is being incentivised is that of further building your influence score to get more freebies. Rewarding influencers does not incentivise the use of influence, it only incentivises boosting your influence score, often by gaming the system, as danah boyd has pointed out.

In addition, even if an influencer decides to use their influence, it is debatable just how much actual impact this will have. At the end of his report, Brian cites four case studies to support his case. One of these looks at how Peerindex (Digital Influence Vendor and a Klout rival) linked-up with UK-based Executive Perks to “identify influential individuals within social networks and invite them into a new lifestyle programme. The programme was designed to provide VIP treatment and preferential rates for luxury merchants and resorts. The audience required consumer qualification to preserve its exclusive brand and appeal… following a very limited wave of 60 invitations, the programme reached over 200,000 people via re-tweets and responses”.

This seems pretty impressive – 60 initial contacts resulting in 200,000 responses. But then I thought, how much of this was down to the fact that the initial 60 were ‘digital influencers’ versus the fact that this was just a well-designed loyalty programme that exploited the fact customer qualification (i.e. that you can only participate via a presumed process of exclusive invitation) is a highly effective response multiplier in this sort of situation? Quite possibly the same effect could have been produced by selecting 60 of their existing customer base at random. If 60 people each invite only two other people this process needs to be repeated 12 times to reach nearly 250,000 people. However, if those same initial 60 reached 10 times as many (i.e. 20 people) and these (now random, ordinary un-influential people) then invite 2 others it still requires this process to be repeated around 7 times to get to in excess of 250,000 people. I.e. starting with the influencers makes things happen a bit quicker, but not that much quicker and the success of the process still largely relies on motivating the un-influential to pass the recommendation on. Thus, success stems from having a motivating proposition, not from targeting an influential group.

Our experience in the viral effect of social networks also supports this conclusion. Things only become viral when un-influential people become involved in passing them on. The influencers may a have a role in getting the process started, but most often viral effects spring-up from the most unlikely, or un-influential sources. It is the nature of what a piece of viral content represents (behaviours and context again) that is the dominant force in driving distribution – not the particular influence of the people who distribute it.

Noel Gallagher of rock band Oasis put it thus when talking about the importance of the music critics and other assorted ‘influencers’: “forget the critics, you only start to make serious money when the squares start buying your records”.

Thus I think we can float the idea that digital influencers may be influential, but probably not that influential. They may be able to push things along a bit more than your average person – but not enough to create a sustained and extensive distribution effect. After-all, once someone has handed the baton on to a ‘normal’ person with a sub-20 Klout score we are back into the realms of the un-influential (the “squares”) again. This further knocks the assumption that the importance of a digital influencer lies in their ability to act as a distributer or multiplier. There may be some exceptions here, but these are likely to concern people we might call super-infleuncers i.e. celebrities. But there is notheing new or especially digital here – seeking celebrity endorsement is a long-established traditional communications tactic.

Thus, I can’t really argue with anything that Brian says in his excellent report. It is all true – provided one adheres to the assumptions on which his definition of digital influence rests. But I think these are false assumptions.

So where does this leave digital influence and digital influencers. I think it leaves us in a similar place to citizen journalism and citizen journalists. Citizen journalism definitely exists as an influential process, but citizen journalists as influential individuals don’t exist (the only people I know who describe themselves as citizen journalists are unemployed traditional journalists with a blog). Likewise, digital influence certainly exists, but digital influencers are over-rated.

This isn’t to say there are not small groups of ‘digitally important’ people you should not be identifying and targeting – it is just that these are not the digital influencers. There are basically two types of important people you need to target. The first of these are the Dave Carrolls of the world – i.e. the people through who via context and behaviour, identify themselves as digitally important people. These people can come from anyone in your target audience, in effect they represent your target audience, but you cannot identify and target them in advance. They are defined by what they are doing at a particular moment in time, not by who they are – these behaviours being things such as raising a compliant, asking a question, commenting on your brand, the competition, the sector.

The second is a group of people who are actually defined by who they are. These are the people who are your brand loyalists: the people, who for whatever reason, have a special passion or interest in your brand. Unfortunately this will only ever be a very small group in relation to your total target audience. Also unfortunately, you will never be able to grow this group to a size where they will make an impact on consumption of your product or service – almost by definition this will be a small and frequently inward looking group. Which means that, unfortunately, you can also forget the idea that these people can become brand ambassadors or advocates. Firstly, the fact that they are passionate about your brand doesn’t mean that they will want to become evangelists for your brand. Despite what WOM advocates might like us to believe, people are not natural evangelists – they only become so in very specific situations: they are either given a significant push or incentive (you will earn some money/points or you won’t go to heaven); or when they find themselves in the presence of other people who share their interest. The people who are natural evangelists we tend to dismiss as tedious bores – unless they happen to be evangelising on a subject to which we are already a convert.

Secondly, if they do want to become evangelists, you probably don’t want to encourage them to do this – either because of the tedious bore factor mentioned above, or because they will come across as strange. There are people so passionate about Coca-Cola that they buy red cars and paint Coke logos on them (I know this to be true for I have seen them on Facebook). However, we don’t make ads about these people because the rest of us see them as weird, and Coke doesn’t want to suggest it is a brand for weirdos.

So what do you do with these people if you can’t increase their number or use them as brand ambassadors? What you do is work out how they can help you do your business. These might want to be the people to involve in new product design for example but their importance in this respect is defined by the knowledge and interest in your brand, not by their digital influence.

Finally, it is also quite likely that there may be communities, rather than individuals, who are genuinely digitally influential. danah boyd has written this very interesting post on how the Kony 2012 video became viral and the role of cultivated communities of young people who fueled the process. Critically though, the focus on these groups was on the creation of the necessary incentive (behaviours and context again) to spread the message, rather than just seeing them as an un-questioning channel. To digress slioghtly, I am already of the view that the community is the new individual. Social media is eroding organisations’ ability to isolate individuals and deal with them in sealed boxes as people discover the power that comes from the ability to connect and share experience. People will only be prepared to engage with organisations within the context of a relevant community, because this context gives them power (but that is another story / as-yet-unwritten post).

So there it is. The digitally important people are not the same as the digitally influential people. And even the digitally influential are not actually that influential. So we can all relax about Klout scores and instead get on with the much more profitable business of focusing on the important people, these being the people that represent your consumers or customers, not those who (supposedly) influence them.

P.S. I haven’t touched on the issue of social profiling. But if I am right about influence, it means that social profiling should focus not on profiling people according to influence, but profiling according to behaviours and context. And this profiling information will only be commercially important if it remains hidden and available only to the organisation building the profile. You don’t want generic Google Goggles to tell you someone has a high influencer score, you want a bespoke set of goggles (an algorithm) that will tell you if someone is, for example, a good credit risk based on the ability to reference a person’s network of friends and cross reference this with a database of credit defaulters. That’s the issue Jason Falls et al need to be looking at, because social data is already being used in this way – it is what I call ‘listening to data’ as distinct from ‘listening to people’. Whilst it uses social data, it is a very anti-social phenomenon (see Huffington Post piece on this).

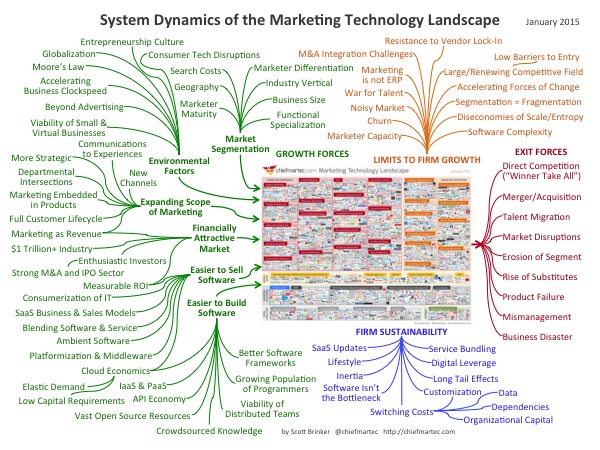

This post is a marker. It is post-it note that says “remember to watch this space and try and get your head around it because this is going to be big”. It also is an excuse to log what I think is a very useful, if slightly mind-bending post by Scott Brinker.

This post is a marker. It is post-it note that says “remember to watch this space and try and get your head around it because this is going to be big”. It also is an excuse to log what I think is a very useful, if slightly mind-bending post by Scott Brinker.

As I have previously observed,

As I have previously observed,