Here is a bold claim. In social media you can’t make money out of individuals, only communities.

Here is a bold claim. In social media you can’t make money out of individuals, only communities.

Here’s why. In the good old days, the way you made money out of media was by being a platform that allowed commercially sponsored messages to be placed in front of lots of individuals. For this to work well, the message had to be be very effective (which is why advertising creative directors made lots of money) and the media had to attract lots of individuals. The more individuals a platfrom could attract, the more money it could charge for its real estate.

This model doesn’t really work in social media, because, as we are slowly starting to realise, platforms such as Facebook are not really media platforms. Facebook can more easily be understood as a tool or an infrastructure. Despite what the film says, it is not a social network, it facilitates social networking. There may be huge numbers of people using the infrastructure – but you can’t reach ‘all of Facebook’ in the same way as you could reach ‘all the readers / viewers’. In reality, Facebook is an eco-system comprised of a vast number of tiny interactions bewteen very small groups of people. This creates a problem, because the commercial opportunity within these types of interaction is highly restricted. In the same way that no-one would want a commercial message inserted into a phone call, people don’t see a role for commercial intervention or interuption in the individual, small scale, relationships people have on Facebook.

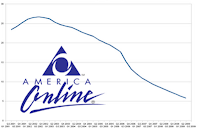

This is a big problem for Facebook, because its current very high valuation is based, in large part, its status as a platfrom that can access millions of people. It has the millions of people, but it cannot provide the access in a way which makes commercial sense and complements the way in which people use the infrastructure. It can only sell itself as an advertising platform, but it is slowly realising that the value of an individual person within Facebook is an awful lot less than the value of an individual reader or viewer. Facebook is coming face-to-face with one of the fundamental rules of commercialising social media: in social media, you can’t make money out of individuals, only communities.

Essentially, there are very few chinks in the armour within individual interactions in social media that allow a credible intervention by an institution or commercial organisation. That is not to say that you should abandon the individual. Listening to individuals and their conversations, and responding where necessary is still a hugely valuable exercise. It is just that 99.99 per cent of all social media activity is un-receiptive to commercial intervention and thus it is just not scalable as a way of reaching lots of people.

However, this starts to change when you stop focusing on the individual and start to focus on the communities that individuals might form (focusing on behaviours, not on platforms or tools). Community is undoubtedly the ‘Next Big Thing’ in social media. The community is the new individual and the community probably represents the only sensible entry or engagement point for most institutions. In working out how to extract commercial value from community it is important to recognise one of the other fundamental rules – which is that individuals will be reluctant to allow themselves to be managed within communities controlled by institutions, rather they will prefer to form communities to manage their relationships with institutions. As people become more familiar with the tools of social media, they will work out how easy it is to create communities that help them ‘do stuff’.

Facebook understands this – which is why it has recently made changes to Facebook Groups and Facebook Pages which are designed to make it clear that Pages are where corporate organisations can have their Facebook outpost but that Groups are for individuals. Facebook is going flat out to encourage its users to aggregate themselves into small communities (Facebook Group functionality starts to de-grade once the Group exceeds 250 members), because it knows that its user base becomes commercially much more valuable as a large number of small communities than as an even larger number of individuals. The problem, of course, is that there are many other tools individuals can use to create communities – many of which are better than Facebook and thus Facebook is in a race a aginst time to try and establish the behaviour of community formation within Facebook in order to try and steal a march on the competition.

This is consistent with Clay Shirky’s assertion that revolutions don’t occur when societies adopt new tools, but when they adopt new behaviours. It is also consistent with Facebook’s objective of being the single tool you use to “do” all your social media, rather than being an application you can use to integrate tools produced by others.

Final bookings are being taken for SMI 2011 which takes place of June 14 in London. This is always a good event, especially for those taking on the responsibility for developing social media within an organisation. It is not an agency-fest and I note the list of speakers this year is heavy on actual social media managers from UK based companies (Sony UK, Tesco, O2) who will be talking about their experience, rather than ‘gurus’ or people with products to sell. Definitely worth attending if you have (or would like to have) responsibility for social media within your organisation.

Final bookings are being taken for SMI 2011 which takes place of June 14 in London. This is always a good event, especially for those taking on the responsibility for developing social media within an organisation. It is not an agency-fest and I note the list of speakers this year is heavy on actual social media managers from UK based companies (Sony UK, Tesco, O2) who will be talking about their experience, rather than ‘gurus’ or people with products to sell. Definitely worth attending if you have (or would like to have) responsibility for social media within your organisation.

LinkedIn has ended its first day of trading as a public company with valuation of $8.9 billion. This is 36 times its 2010 revenue. That’s right – 36 times revenue. As

LinkedIn has ended its first day of trading as a public company with valuation of $8.9 billion. This is 36 times its 2010 revenue. That’s right – 36 times revenue. As Last Friday I spend the day at the Plantijnhogeschool in Antwerp, giving the keynote speech at a conference organised by the

Last Friday I spend the day at the Plantijnhogeschool in Antwerp, giving the keynote speech at a conference organised by the  A couple of weeks ago I was in Sofia, Bulgaria, to run a workshop and speak and the annual gathering of advertising and media folk, organised by the Bulgarian Assosication of Advertising Agencies. I was doing this wearing my hat as a member of the faculty of the

A couple of weeks ago I was in Sofia, Bulgaria, to run a workshop and speak and the annual gathering of advertising and media folk, organised by the Bulgarian Assosication of Advertising Agencies. I was doing this wearing my hat as a member of the faculty of the  Continuing the Facebook / business model theme,

Continuing the Facebook / business model theme, Here is a bold claim. In social media you can’t make money out of individuals, only communities.

Here is a bold claim. In social media you can’t make money out of individuals, only communities.